My Year of Classics Part One: Paradise Lost

Or, the magic of little free libraries and reading aloud

Please note: this post will be cut off in email. There should be a link at the bottom to read on browser, or you can read in the Substack app/on the Substack website. Also, if you are reading along, this post concerns books one and two of Paradise Lost.

Hello and happy (?) new year!

If you missed my last post and are confused as to why I’m writing to you about Paradise Lost, I am embarking on a “year of classics.” My challenge to myself is to read one piece of classic literature and watch one classic movie (the latter being much easier than the former) per month, in an effort to increase my attention span and live my days the way I’d like to live my life. Because (not to get too existential) days are all we have, baby!

For the first month of the year, I’ve chosen Paradise Lost, because I am a masochist and it was on my shelf from when I found it in a little free library and thought, “I should read Paradise Lost one day!” I’ve come to believe that this thought is equivalent to the serpent tempting Eve with the apple (I’m not there yet in the book, so no spoilers! She might not eat it this time!).

I’ve watched a number of YouTube videos/read a few articles on how to read Paradise Lost, since it is extremely intimidating, but the advice I resonated with most was from a video by Dr. Adam Walker, a Harvard English professor. He was quoting Charles Osgood, who wrote the following: “I find it a present habit of students—superinduced, I think, by a generation of teachers too far gone in bibliographomania [obsession to read all the critics]—to scant their scrutiny of an author’s works and run off in search of something about them.”

oKAY!!!! I’ve been called out!

This is almost always what I find myself doing, though I will say on my part it’s more to do with the fact that I’m deeply interested in authors as human beings, sometimes even more so than their work (see: my obsession with Vita Sackville West when I’ve never read anything of hers other than her letters to Virginia Woolf).

Charles Osgood then goes on to say (re: reading Milton), “Let inclination and curiosity be your guides. Mark your favorite passages. Get them by heart. You are embarked on a romantic voyage of discovery. Enjoy the music and the spectacle, and ponder the meaning. What you discover by yourself is worth over and over what any authority can tell you. And if you look long and singly and humanly enough at the poem, probably you can tell the authority something.”

I love this, and, while I will almost definitely not understand most of the poem, and while I can’t stop myself from Googling at least a little (you can’t tell a bird not to fly etc.), I will try to let this incomprehensible poem flow over me and enjoy the “romantic voyage of discovery.”

(Side note that is not really a side note at all: my romantic voyage led me past a little free library in which someone had left their King James Version of the Bible, which was most likely the version Milton would’ve read, and I’d like to read Genesis along with the poem as a fun side quest.)

On January 2nd, I began my voyage with Book One (the epic poem is divided into twelve books), which is basically devoted to making Satan seem like a sick hang. I read it aloud to myself while Daniela was out, and an annotation I wrote on lines 545 through 560 sums up my experience: “Honestly IDK what’s happening but it sounds pretty when I read it aloud.”

Who would’ve thunk, one of the most formative poems in the English language SOUNDS NICE TO READ?! Shocker, I know.

As I mentioned before, Satan comes out of this first book looking exceedingly cool. In one of my annotations, I called him a little scamp. I mean, just listen to what he says to his second-in-command, Beelzebub:

“Fall’n Cherub, to be weak is miserable

Doing or suffering: but of this be sure,

To do aught good never will be our task,

But ever do ill our soul delight,

As being the contrary to his high will

Whom we resist. (I.157-163)

Basically, he’s saying, “Let’s be bad! Let’s do everything God doesn’t want us to do!”

Earlier in the poem, in a famous line, Satan (EDIT FROM JAKE WHO IS CURRENTLY READING BOOK FIVE: I said he is only known as Satan in Heaven, but actually he is only known as Satan OUT of Heaven. Apparently he had a former Heavenly name which is no longer spoken) says, “All is not lost; the unconquerable will,/ And study of revenge, immortal hate,/And courage never to submit or yield” (I.106-108).

I kind of love how he’s basically a bitter old queen.

There is something undeniably queer about Satan, which tracks because he’s literally a fallen angel. If we’re going by the Merriam-Webster definition of “differing in some way from what is usual or normal,” then Satan is definitionally queer. He is not normal—he has fallen, he has queered the idea of what an angel is or can be.

But his queerness is in more than that: it’s also in the way he talks, in his dramatics, in the aesthetics of hell (the book starts with him lying on a burning lake).

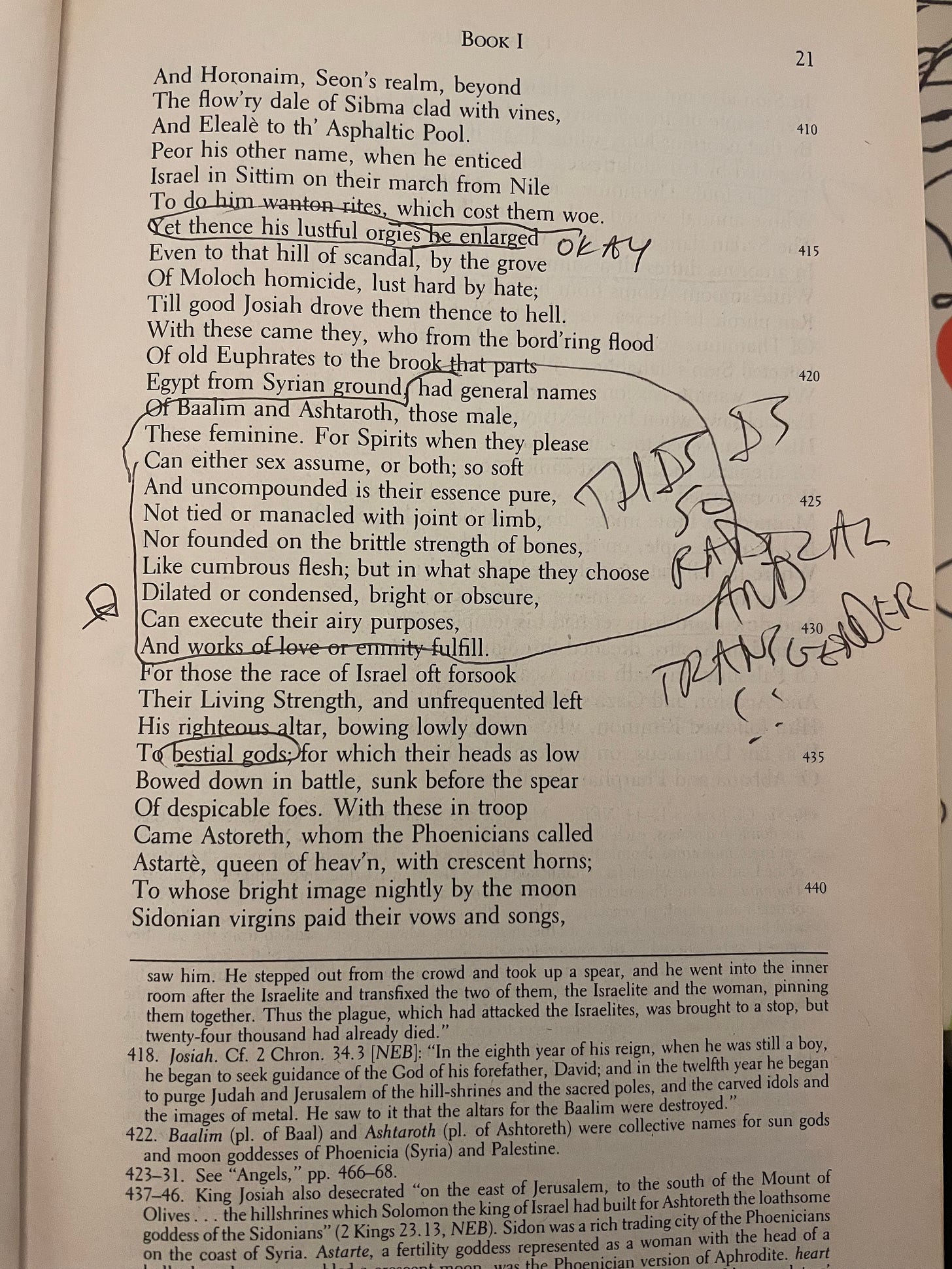

Then, there’s his legion of fallen angels, who Milton documents for like 200 plus lines, and include these trans icons:

With these came they, who from the bordring flood

Of old Euphrates to the Brook that parts [ 420 ]

Egypt from Syrian ground, had general Names

Of Baalim and Ashtaroth, those male,

These Feminine. For Spirits when they please

Can either Sex assume, or both; so soft

And uncompounded is thir Essence pure, [ 425 ]

Not ti'd or manacl'd with joynt or limb,

Nor founded on the brittle strength of bones,

Like cumbrous flesh; but in what shape they choose

Dilated or condens't, bright or obscure,

Can execute thir aerie purposes, [ 430 ]

And works of love or enmity fulfill.

I don’t fully understand this part (or, really, any of it), but I’m not too worried about that, because in my lack of understanding I am allowed to be amazed by the fact that there are random nonbinary demons in the text.

John Rogers called the description of the angels’ gender as “gratuitous,” which I love, because there is something so sumptuous about spending many, many lines describing queer Pagan spirits.

Something that really struck me in this first book is the way that the other fallen angels still respect Satan, even though the war that he waged in heaven is the reason that they are condemned to eternity in Hell.

Millions of spirits for his fault amerced

Of heav’n and from eternal splendors flung

For his revolt, yet faithful how they stood (I. 609-611)

There’s something magnetic about Satan. He ruined their lives, but they still love him, or at least are faithful to him. I couldn’t help but think of cult leaders, whom people praise (or at least mention how charismatic they were) even after they’ve left the cult. He may be evil, but he is an amazing speaker, a leader. I’ve read that many people consider Satan to be one of English literature’s first “anti-heroes,” and I can see that clearly in lines like these.

As I was reading the first book aloud, I noticed that, even though I was doing two actions (scanning the page and vocalizing), my mind could somehow wander. This mostly happened when there were many lines I didn’t understand. It’s almost impressive how deeply my brain (and I have to imagine others’) searches for stimulation. I was thinking about the episodes of Drag Race Daniela and I were watching, or a part of the draft of my middle-grade novel that’s stumping me, or any number of things.

But then there are some passages where I get so into the reading, passages that can’t help but hold my attention. This, from book two, is one of them:

Let us not then pursue

By force impossible, by leave obtained

Unácceptable, though in heav’n, our state

Of splendid vassalage, but rather seek

Our own good from ourselves, and from our own

Live to ourselves, though in this vast recess,

Free, and to none accountable, preferring

Hard liberty before the easy yoke

Of servile pomp. (II. 248-257)

Not only are there so many lines that feel amazing in the mouth when spoken aloud (“splendid vassalage,” “servile pomp”), but the idea behind it is also amazing. The idea that it is better to be free in hell than in bondage in heaven.

So much of this poem is concerned with free will and liberty, which makes sense since Milton was a Puritan not in the sense that we know it now but in the sense that he was out here arguing in favor of regicide (icon!).

For the most part, book two is a meeting of many of the fallen angels, who state their case as to whether or not they should wage war anew in heaven. None of it actually matters in the end, because Satan has another idea (can you guess what that is)? But then the end of the book is a SHARP departure, where Satan is trying to leave through the gates of hell and his daughter/lover Sin is trying to stop him in a really sexual and sort of Mother way.

In this book, hell is also described really beautifully by Milton, especially when Satan sets out on his quest.

Beyond this flood a frozen continent

Lies dark and wild, beat with perpetual storms

Of whirlwind and dire hail (II. 587-589)

It’s also described as “a universe of death” (II. 622), which is so evocative.

The next 600 or so lines include Satan’s run-in with the daughter he forgot he had in heaven, who he also impregnated (don’t worry about it). She is described (I believe it is her, correct me if I’m wrong), as “woman to the waist, and fair,/But ended foul in many a scaly fold/Voluminous and vast” (II. 650-652). Hell truly is populated with so many characters who fall outside of the binary of man and woman, which is interesting because we’re about to meet the FIRST man and the first woman (though I haven’t gotten there yet, again, no spoilers) (mostly kidding).

Also, if I ever feel bad about my run-on sentences, I can refer back to Milton. (This is an aside, but I’ve learned that he, from a young age, called his shot and said he would write an epic poem and would be famous and remembered. Iconic.)

But what owe I to his commands above,

Who hates me, and hath hither thrust me down

Into this gloom of Tartarus profound,

To sit in hateful office here confined,

Inhabitant of Heaven and heavenly born,860

Here in perpetual agony and pain,

With terrors and with clamours compassed round

Of mine own brood, that on my bowels feed?

Thou art my father, thou my author, thou

My being gavest me; whom should I obey

But thee? whom follow? (II. 856-866)

Other than being an extremely long thought, I also love Sin calling Satan her author. There’s something really beautiful and a little gross about that, especially since he also got her pregnant with a boy who would become Death (metal).

This book also contains the phrase “His dark materials,” which really was a big “HE SAID THE NAME OF THE SERIES!” moment for me as a fan of Phillip Pullman’s books. I’m excited to reread those after reading this, since so much of the series references Paradise Lost. The entire quote in context is this:

Into this wild Abyss

—The womb of Nature and perhaps her grave,

Of neither sea, nor shore, nor air, nor fire,

But all these in their pregnant causes mixed

Confusedly, and which thus must ever fight,

Unless the almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more worlds—

Into this wild Abyss the wary Fiend

Stood on the brink of Hell and looked awhile,

Pondering his voyage; (II. 910-919)

I love the image of Satan looking out on his domain for one last time before heading to this new realm of “earth.” So much of this poem so far has just been really cool images that I can sort of picture, but not quite.

The longer I read aloud each session, the more I get into the characters and the language, and the more I understand. Hopefully that continues throughout each book, and by the end I’ll be so smart that I could teach a course on Milton (this will never happen).

Speaking of courses on Milton: there are some amazing resources on YouTube that have really enhanced my experience reading. I try to read the section first and then watch the video, because I don’t want the thoughts of someone significantly smarter than me to influence how I read the text (I am easily influenced).

This course on Milton is free through Yale on YouTube, and I am obsessed with the lecturer, Dr. John Rogers.

There is also the series Dr. Adam Walker (mentioned above) has called Paradise Lost in Slow Motion.

If you’ve read Paradise Lost, or taken a course in which you read it, send me your thoughts or resources!

Also, if you’re reading along, comment below your favorite lines/thoughts/how iconic you find Satan.

Next up, books three and four of Paradise Lost!

All my best,

Jake